In 2014, the year of celebrating a 200th anniversary of Oskar Kolberg birth, I accomplished the work on the first part of my book entitled Zachować dawne nagrania. Zarys historii dokumentacji fonograficznej i filmowej polskich tradycji muzycznych i tanecznych1 (Preserving old recordings. A historical outline of phonographic and film documentation of Polish music and dance traditions). I also performed a preliminary analysis of resources and availability of the archival recordings documenting Polish music traditions whose results were published in a jubilee Report2. Simultaneously, a text summarising the works and changes taking place in the Phonographic Collectionof The Institute of Art of Polish Academy of Sciences was being written after a decade of this historical collection functioning in the developing digital reality.3 I realised how little – paradoxically, in the era of unlimited access to information – we know about our ethno-phonographic national heritage, both archival and contemporary. I realised that, despite one century having passed by, we have not moved forward in many areas that for so long have been underlined by scientists who created the foundation of Polish comparative musicology and music ethnography (at that time using the phonograph in order to create research resources) in Polish soil, however belated compared to the rest of Europe (due to the national captivity). Among the scientists there should be mentioned Adolf Chybiński, Juliusz Zborowski, Łucjan Kamieński, Julian Pulikowski. I have described their input into the history of Polish ethno-phonography in the book Preserving old recordings. I was especially impressed by the thoughts formed by Juliusz Zborowski, most probably still before regaining independence, and published in the inter-war period. One sentence among others said, „We do not have […] a central facility that would collect all of Polish folk music, we do not have »a Polish phonographic archive«” 4.

In 2014 we still did not have such facility… The knowledge of persons in question, including specialists, on the availability of archival recordings serving as sources for scientific research was limited at the time to the awareness of the existence of the oldest and the biggest Polish collection of historic recordings of traditional music – The Phonographic Collection of The Institute of Art of Polish Academy of Sciences (ca. 150,000 recordings) as well as some other collections, such as the collection of The Institute of Musicology of The Catholic University of Lublin, the Lab of “Ethnolinguistic Archive” of the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, as well as radio archives. I recall my conversations with professor Jan Stęszewski who repeatedly advanced a demand for another – after fifty years – national Musical Folklore Collecting Campaign first organized between 1950 and 1954, results of which are a foundation of above mentioned Phonographic Collection of The Institute of Art of Polish Academy of Sciences.

Juliusz Zborowski (1888-1965) and Adolf Chybiński (1880-1952). Zakopane 1927. Photo - Marceli Skibka. The picture from the collection of Dr Tytus Chałubiński Tatra Mountains Museum in Zakopane.

Jan Stęszewski (1929-2016). Photo - Piotr Dahlig, Radziejowice 1991.

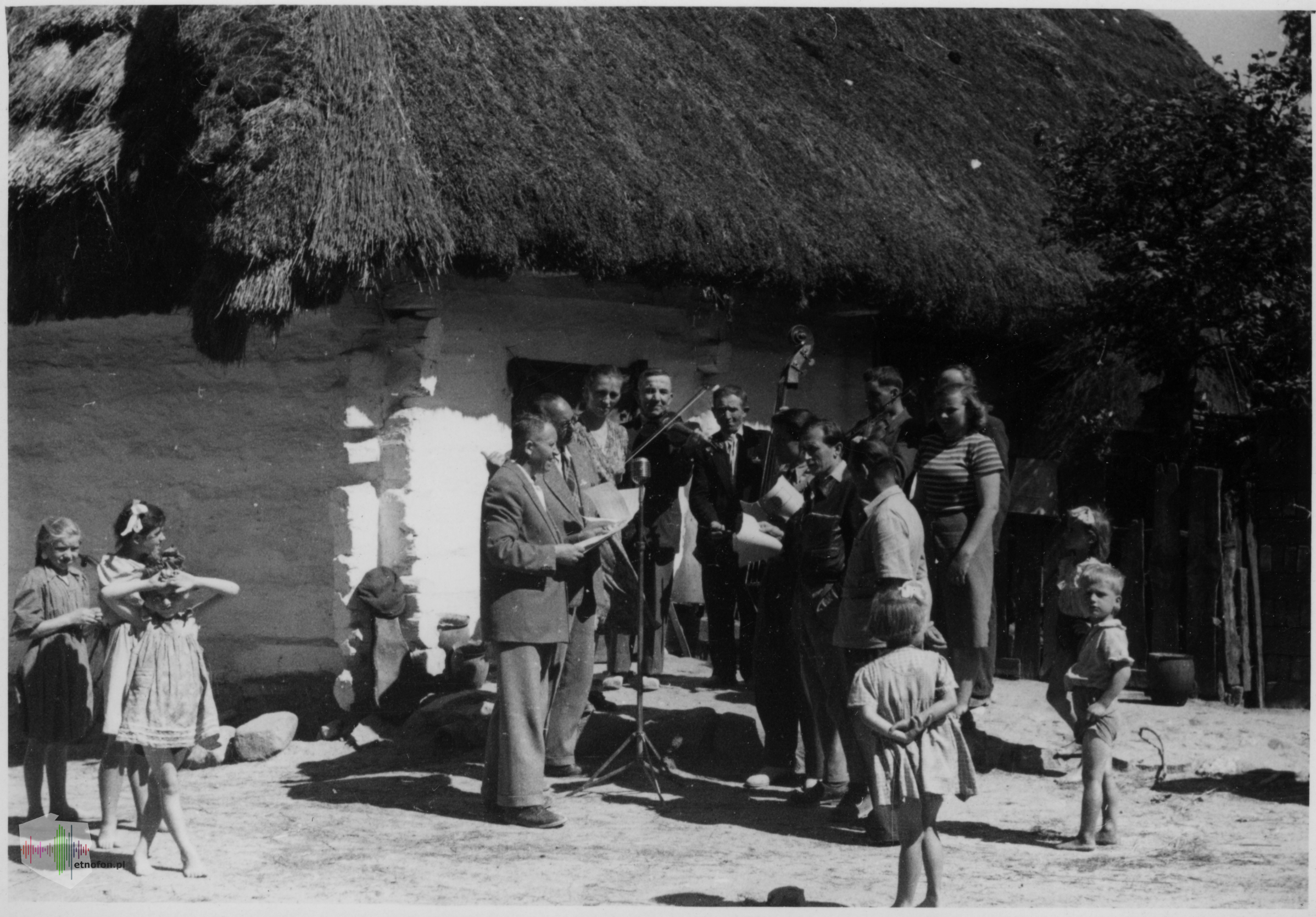

The team of Kielce Musical Folklore Collecting Campaign During taking the recordings. Słupia, county of Jędrzejów, May 1952. Author unknown. Pictures from the The Phonographic Collection of The Institute of Art of PAS.

The demand is absolutely legitimate, however we must not forget that in the second half of the past century, especially since the 1970s, the availability of recording equipment grew larger, and recording itself was becoming more and more popular form of activity for many researchers and regionalists.

If still in the 1950s the National Institute of Art due to the cooperation with Polish Radio could count on technical support in order to carry out a large-scale documentation project, yet several years later almost every ethnomusicologist, ethnographer or folklorist was able to take their own recordings thanks to a growing popularity and availability of the tape recorder, however, at first it was still a rather costly challenge (oh, the things we do for pursuing our passion!). Institutions and people devoted to the matter were numerous: Roderyk Lange, Jarosław Lisakowski, Anna Szałaśna, Franciszek Kotula, Aranuta Ada Radzikowska, Wacław Tuwalski, Marta Brzuskowska, Wanda Księżopolska, Maryna Okęcka-Bromkowa, Piotr Dahlig and many others.

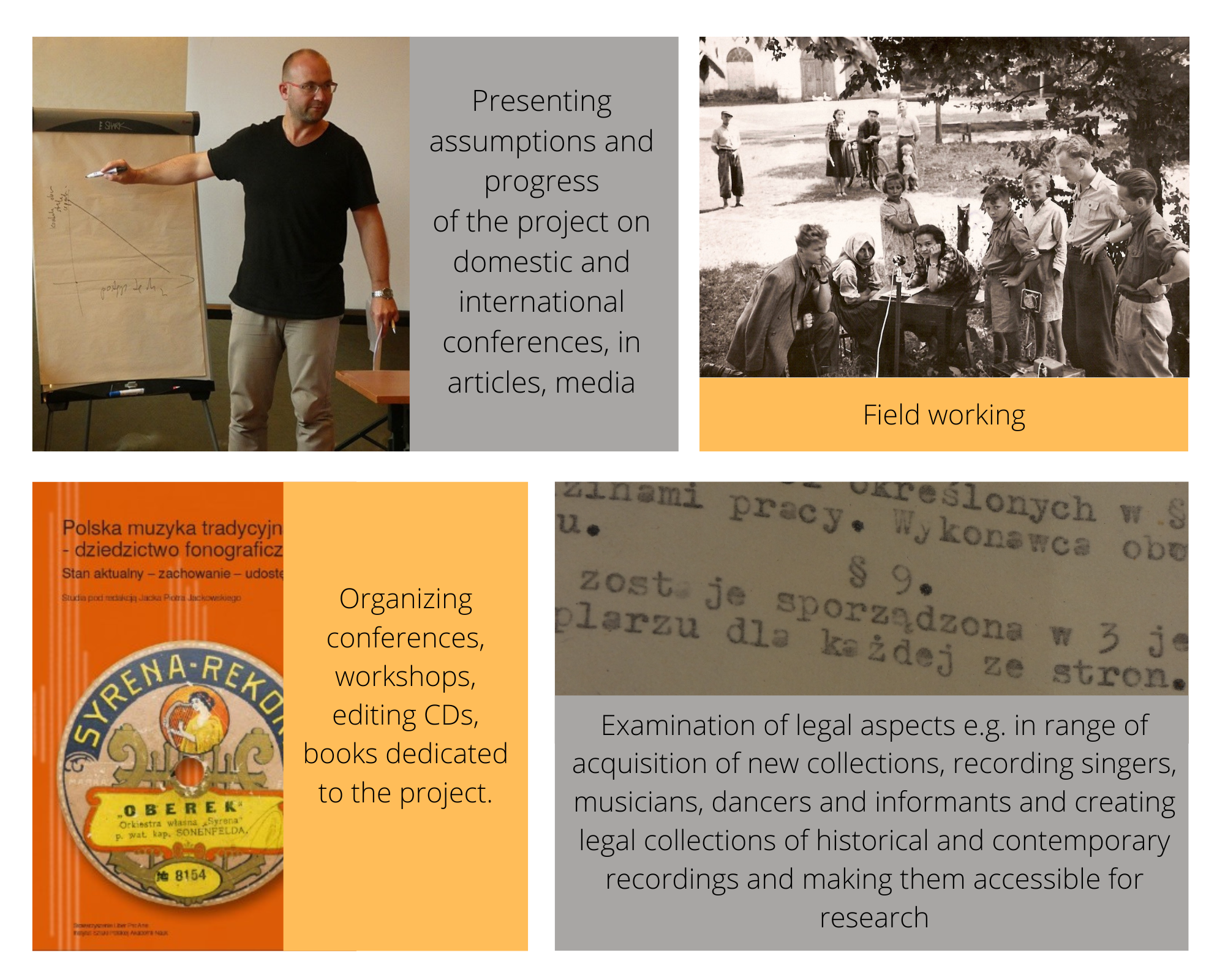

Therefore, however seemingly independent documentary works of various institutions and researchers were not centralised, and often of an individual character, they were usually and largely based on a methodological model worked out by Jadwiga and Marian Sobieski and their numerous co-workers who took part in the Campaign. This is why I presented a proposal5 that we should (before organising another edition of the national Musical Folklore Collecting Campaign) focus our efforts on recognising, identifying, examining, digitising, elaborating, archiving and centralising the already existing ethno-phonographic heritage in one, national digital repository6. This is an overriding aim of the project entitled Polish traditional music – a phonographic heritage. The present state, preservation and sharing.

PhD Jacek Jackowski – the author and corrdinator of the project

Polish traditional music – a phonographic heritage.

The present state, preservation and sharing.